Text and photography | Martin PÜSCHEL VON STATTEN

Hardly any other building material divides people more on the question of what »is beautiful« — not to mention its image; only asbestos would suffer from greater depression if it could feel anything. And yet, for around 2,000 years, its technological development has shaped the aesthetics of urban space like no other material. The almost endless possibilities of its shaping nourish the dream of overcoming gravity and create its bipolar nature. Thus he gives us a grandiose bridge structure that spans a wide valley in a tender gesture. Just around the next bend, however, he cuts a swath of devastation through a baroque old town, his corset embraces a once meandering stream and degrades it to a hydrodynamic death zone. Concrete. It all began so beautifully.

INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY, Kiev, F. Yuryev and L. Novikov, 1971, © Martin Püschel von Statten

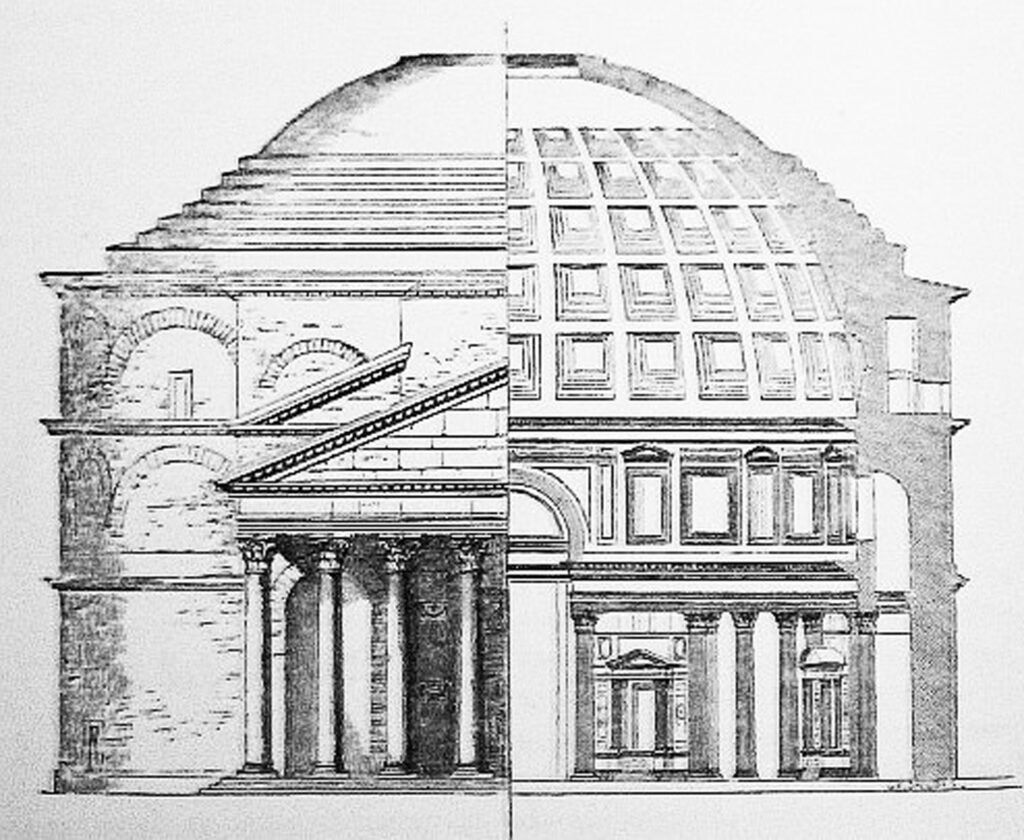

The light of the sky burns brightly through a huge hole in the ceiling, through which the gods of antiquity look out at the perplexed audience. A grey firmament with a diameter of around 43 meters, completed around the year 128, arches majestically above the astonished spectators. At that time, Vienna was the Roman border fortress of Vindobona, behind which Barbaricum lay, and Berlin was nothing more than the distant future of a swampy expanse full of mosquitoes. No pillar supports this construction, which was only completed a good 1,800 years later by the Hala Stulecia (Hall of the Century) in today’s Wrocław as the largest domed building in the world. Anyone who has ever entered the Pantheon in the center of Rome in awe and furtively thought that this technical masterpiece looked like concrete can rest assured: it is concrete.

PANTHEON, inner dome, Rome, around 128 AD, © Martin Püschel von Statten

BERLIN-MARZAHNICUM

The Pantheon in Rome is no exception; on the contrary, concrete was a decisive factor in the expansion and survival of the Roman Empire. Temples, palaces and viaducts were built quickly, cheaply and with a long lifespan using a building material that seemed utopian for the time. As sobering as it may sound to fans of ancient architecture, the reason why even the Colosseum still stands today is a simple one: concrete. The Romans used a mixture of burnt lime, water and additives such as tuff or broken bricks to produce calcium silicate hydrate. They called this predecessor of modern concrete opus caementitium and had been using it as mortar since the 3rd century BC. Later, entire buildings were made from it, »thick at the bottom, thin at the top« was the formula for the corresponding stability. Since, unlike today, there was no steel reinforcement in the concrete, nothing could rust inside and eventually collapse. As a result, the impressive buildings are still standing today, wind and weather cannot harm them, and even in 2,000-year-old wall plaster there is not the slightest crack to be found to this day. As exposed concrete was apparently not in vogue with the Romans, most of the buildings were clad with a wide variety of stones. From the outside, theaters, arenas and the like look like solid masonry monuments, beautiful, aesthetic, admirable. It’s all just a facade. Rome is the ancient version of Berlin-Marzahn.

Pantheon, sectional view; James Ferguson, A History of Architecture in All Countries 3rd edition.

Ed. R. Phené Spiers, F.S.A. London, 1895 Vol. I, p. 320, Public domain on Wikimedia Commons

With the fall of the Roman Empire, darkness once again descended on Europe. People retreated into holes in the ground and wooden shacks, forgetting what toilets were and, accordingly, that concrete ever existed. It was not until the middle of the 18th century that concrete was rediscovered, in England, the northernmost part of the former Roman Empire. Initially conceived as a waterproof mortar, a modern building material quickly developed, from which the first buildings were to be constructed using tamped concrete. The decisive breakthrough came with the Frenchman Joseph Monier, who patented reinforced concrete in 1867. He paved the way for the progressive technological development of concrete, which is now used to build the tallest and longest structures known to man using water, sand, cement and steel.

Concrete trowel of the »sails« of the SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE, Jørn Utzon, 1959 – 1973; Dr. Frank Köhler. Sydney Opera House;

GRAVITATION AS THE BOUNDARY OF POWER AND GRACE

Beyond being fast and cheap, concrete developed into a political issue, similar to the Roman Empire. The planned rebuilding of entire cities between Naples and Berlin, even implemented in small parts, would have been unthinkable without reinforced concrete. But no matter which political system prevails: tanks roll particularly well over concrete roads, the more exciting the construction, the greater the appreciation of its creators and financiers. Those who think highly of themselves also build a phallus in the urban landscape where there is no shortage of space, expensive and powerful, right up above the clouds. War-ravaged Europe became a playground for the dawn of modernity, entire metropolises were rebuilt in record time, satellite cities were erected and sensational prestige buildings for administration and culture were created, which – depending on political taste and zeitgeist – were intended to manifest the superiority of a system through their extraordinary elegance or massiveness. This is particularly evident in the states of the former Soviet Union. After Stalin and the confectioner’s style became obsolete, Moscow proclaimed a new aesthetic, for which the properties of concrete and its visible materiality played a prominent role: Thanks to reinforced concrete, futuristic buildings emerged, graceful, self-supporting and as visible proof of a modern society turned towards the future. On the other side of the planet too, in Brazil for example, elegant to almost daring concrete constructions bear witness to a progressive self-image. A high aesthetic standard and an unshakeable belief in progress have become a built reality before the eyes of the global public. Buildings for culture and religion exhibit a very similar phenomenon. Whether in the sweeping, soaring sails of an opera house or in the edgy, massive church buildings of post-war modernism – concrete was and is deliberately used as a contemporary and aesthetic stylistic device to create a sublime space of the highest grace.

Pilgrimage church Maria Königin des Friedens, Neviges, Germany; Flickr gottfried böhm, pilgrimage church, neviges 1963 – 1972, seier+seier. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

At the same time, the almost free form of the building material offers an effective means of representation both internally and externally. Government buildings that even play with visible concrete surfaces follow the same principle. In Brasilia, for example, an entire capital was cast in concrete; in Berlin, a massive ribbon of the federal government stretches from east to west in velvety-looking exposed concrete. The construction of apartments for 20,000 people by the GDR in Zanzibar flourished in the 1960s: in return, Zanzibar recognized the GDR as a sovereign state.

In addition to reinforced concrete, the ferrocement construction method, which had been refined since the 1920s, was the starting point for new forms in architecture. The shell construction resulted in curved concrete shells that were self-supporting. The filigree dome of the Zeiss Planetarium in Jena, Thuringia, was the driving force behind built utopias. With a span of 25 meters, the shell is only 6 centimeters thick. Concrete, wafer-thin and stable as never before, created in 1926. In the following years, and especially after the Second World War, the shells reached ever greater spans, from pavilions to congress halls, spaceship-like structures grew into urban spaces worldwide. One of the best-known architects of so-called hypar shell buildings was Ulrich Müther, who adorned the cities and communities of the GDR with futuristic functional buildings such as canteens and exhibition halls. The elaborate technology of the hypar shells harbored a paradox of sorts: it brought a forward-looking aesthetic to every corner of the country, in which the old towns were increasingly falling into disrepair and the carefully planned large housing estates (until German reunification) often remained monotonously designed and monofunctional.

RETTUNGSTURM 1, Binz, Rügen, Germany, Ulrich Müther, 1981; Müther Archive Association, Annika Janke, Wismar University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Design

TYPICALLY INDIVIDUAL

This brings us to the Plattenbau, the horror image of all those who today pay a lot of money to live in the former slums of the Wilhelminian era. Even if we don’t venture out of the pigeonhole into which we put prefabricated housing … no dystopian film dispenses with the aesthetic stylistic device of the ever-same and eternal gray; it casts a spell over us. Grids and repetition exert their own fascination on people, which is another reason why the prefabricated building can be included in the series of remarkable building types. In German-speaking countries in particular, prefabricated housing is often the subject of one-sided media coverage and has become, quite wrongly, a symbol of poverty and decline. Whenever social problems are reported on in Switzerland, Austria or Germany, the following agency image appears again and again in newspapers and news programs: Little girl in pink jacket sitting sadly on a dilapidated fence, gray prefabricated buildings in the background. The fact that millions of people around the world live very happily in the »Platte« is completely ignored.

Les choux de creéteil »Cauliflower settlement«, Créteil near Paris, Gérard Grandval, 1969—1974, © Martin Püschel von Statten

Buildings and urban structures emerged around the globe, representing national pride in technical achievements in the form of typified housing. Residential buildings were built that aspire to the stars like rockets or imitate flowers in their floor plans. Some cities, such as Vienna and Genoa, experimented in type construction with »housing machines», which despite their massive bodies – and thanks to the possible formwork shapes of the concrete – have a high design standard and undoubtedly enable high-quality living in sometimes exciting buildings. Furthermore, the technological developments in concrete also made it possible to create regional aesthetics in mass housing construction, where the design of the type buildings is based on brick Gothic or Islamic floral ornamentation, for example. The evolving technology of infra-lightweight concrete (ILC) offers completely new possibilities in urban and residential construction. Conventional concrete has to be insulated with an additional material, which means that a building consists of several layers. Even exposed concrete thus becomes just a shell, which makes neither economic nor ecological sense. ILC, on the other hand, combines statics and thermal insulation. So-called expanded glass, which is produced by foaming used glass, makes the stable concrete particularly light. Tiny air pores provide the necessary insulating properties, as air is a poor conductor of heat. Now that smaller buildings have already been constructed with ILC, plans for high-rise buildings made of the new material are well advanced. Various institutions and engineering firms are experimenting with the use of specially shaped, prefabricated elements, which in turn open up completely new paths in type construction. As the private and public merge into a single unit in terms of materiality, the technical innovation of infra-lightweight concrete becomes a test of aesthetic perception: Exposed concrete is the defining element in both urban spaces and intimate living areas.

CHEONGGYECHEON, a recreational area around 11 kilometers long in the center of Seoul, after the highway was demolished in 2005, © Martin Püschel von Statten

WITH ALL MY LOVE …

… we need to talk. About the fact that the forests of the Roman Empire were burned in the lime kilns that made the construction of ancient metropolises possible in the first place. We need to talk about the countless beaches and riverbeds of our planet that are being transformed into highways by concrete mixers or growing into the sky in the form of skyscrapers so that the gods no longer have to look at their creation through a hole in the concrete lid. At eye level with the universe, the industrialized world celebrates progress and with it the fairy tale of limitless growth that blocks the view of finite resources. Sand is one of these. As early as the 1st century BC, the Roman master builder Marcus Vitruvius Pollio wrote that good sand must crunch between the fingers for building. Desert sand does not do this – but sand that has become a massive problem for the stability of entire coastal regions due to overexploitation; the construction boom does not even stop at protected river systems. The suction trunks of specially designed boats provide the building materials industry with supplies, which are inexorably dragging the habitats of flora and fauna into the abyss through erosion. And thus also those of humans. Another sticking point is CO₂, as the cement industry produces at least 7 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. On the one hand, energy production for burning lime consumes large quantities of fossil fuels, and on the other, the greenhouse gas is also produced by the chemical reactions in the cement.

We will not be able to do without concrete as a building material for the foreseeable future. The younger generation in particular is called upon to publicly question the prevailing policy: Answers are provided by the increased mix of materials, exclusively recyclable insulation materials and the promotion of timber construction. Wood is very durable and flexible, it is a renewable raw material, binds large amounts of CO₂ and can be reused. Concrete should only be used where it is really necessary, for example in building cores and bridge structures. New technologies allow innovative type elements and now even high-rise buildings to be made of wood. This does not detract from the aesthetics, as wood also adapts to many shapes, and the individuality of a building is retained through the appropriate façade design. Cities will continue to grow – with the increased use of natural building materials, we can help to harmonize high-quality architecture and ecological construction.

Built with everything that was there: ROMA-VILLA, Soroca, Moldova, © Martin Püschel von Statten