Eileen Gray’s attempt to create a discreet yet avant-garde refuge for herself led to a conflict—and to a story that, like few others, tells of the expression of female self-determination and societal expectations. The documentary film »E.1027—Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea« approaches this fascinating chapter of architectural and design history in a sensitive yet visually powerful way.

»A house is not a machine to live in. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation«—this is how the Irish-born architect and designer Eileen Gray once summed up her understanding of architecture. What lies behind these words becomes clear when one takes a closer look at her first house, a masterpiece as discreet as it is avant-garde, named »E.1027«. Gray built the villa, located on the Côte d’Azur, in 1929 as a refuge for herself. The name is a cryptic combination of her initials and those of the journalist and architect Jean Badovici, with whom she built the house. Originally, it was conceived as a place that would allow them to hide from the world, if necessary, but also from each other. While its flat roof and clear lines clearly corresponded to the spirit of modernism, Gray added a sensual-intuitive layer to the design, which ultimately meant that »E.1027« had nothing to do with Le Corbusier’s coined term of the »living machine«.

Painted over and appropriated

Gray began her career as a lacquer artist, but gradually evolved into a designer and interior architect, creating design icons with the »Adjustable Table E 1027« and many other designs. Not only her refuge on the Côte d’Azur, but also her furniture and furnishings testify that Eileen Gray was far ahead of her time. Long before Mies van der Rohe, the artist, who grew up in an aristocratic family in County Wexford, Ireland, experimented with tubular steel furniture. The »Non Conformist Armchair« (1926) was an important piece of furniture of its time not only because of its formal language, but also because of its statement, which perfectly matched the attitude of its creator: One side—the one with the armrest—was for leaning back and smoking, the other allowed for the freedom needed when gesturing and discussing.

Eileen Gray’s connection to Jean Badovici and his extensive network led, among other things, to several encounters with Le Corbusier, who could barely conceal his enthusiasm for »E.1027«. After Gray decided in the early 1930s to leave the house to Jean Badovici, he encouraged Le Corbusier to cover the interior and exterior walls of »E.1027« with imposing frescoes. Eileen Gray, who had deliberately used white, bare walls as a stylistic device, was not informed about this. She described the paintings as vandalism and demanded their removal, but her wish was ignored. Le Corbusier instead built his famous »Le Cabanon«, a rustic-looking log cabin, directly behind »E.1027«. With her departure from »E.1027« in 1931, Eileen Gray also withdrew from the public spotlight. She died in 1976 at the age of 98. Her furniture and furnishings are now traded at high prices and are represented in numerous museums and exhibitions. »E.1027« is accessible to the general public as a museum.

Formulas are nothing

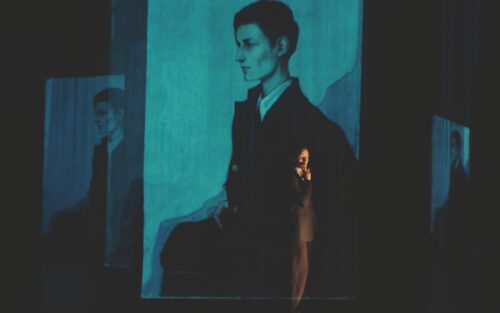

The film »E.1027 — Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea«, which was filmed, among other locations, at the original site of »E.1027« in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, reconstructs the dramatic story of an avant-garde designer and her refuge, which turned out to be a masterpiece. Gray’s design language was also the direct inspiration for the film’s creation, which also tells of the challenges Eileen Gray had to face as one of the first female architects of the modern era to pursue her passion. Since Eileen Gray had her private correspondence destroyed, »E.1027 — Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea« is a film that approaches the person through her work.

»At the heart of this film is an unresolved conflict. One could argue that Le Corbusier did nothing wrong. Eileen Gray was already gone when he appeared. Jean Badovici gave him permission for the murals and even encouraged him. But is it okay to violate and appropriate another artist’s artistic vision? Of course not, I would argue,« summarizes director Beatrice Minger the core conflict. »Le Corbusier did not appropriate Gray’s house because she was a woman. He could not bear her different perspective her deep sensibility, her artistic power, her freedom—and had to make it his own.«

Eileen Gray formulated it as follows: »Formulas are nothing. Life is everything. And life is simultaneously mind and heart.« [SW]