Text Andreas K. Vetter

As is well known, we are in the midst of an automotive »paradigm shift«: New drive technologies are changing vehicle design, for example, because batteries and electric motors require different spatial arrangements within the bodywork. Another indication of change is the tendency for automotive groups and manufacturers to numerically reduce the sales and maintenance services previously provided through brand dealerships and authorized dealers, and to significantly modify presentation areas. A lot is therefore in motion, and for all involved — from engineering to design, marketing, and infrastructure providers, right up to the customers. But such a »paradigm shift« is not new. With a little courage to look back at history, one can go back over 100 years and find oneself in the midst of a veritable revolution in mobility.

This can be experienced in an inspiring way at the Stuttgart Mercedes-Benz Museum. Here, in the first room of the exhibition, one stands opposite a millennia-old vehicle, or rather, companion of humankind — the horse. And then come the ancestors of the car: still carriage-like machines. The threshold of transition from the old to the new era is very broad in Europe and had to be overcome over many years until comprehensive mechanization.

The spread of the automobile into society proceeded very differently, which is understandable in the first decades due to the high prices and complex technical maintenance. Initially, the wealthy classes owned the new mobile, and among the protagonists of this movement, then still understood as a fashion, were also ruling princes such as the German Emperor or the Russian Tsar.

Within this mobile revolution, it eventually took some time until producers began to think about the first professional sales rooms, the precursors of today’s authorized dealers and showrooms. Initially, manufacturing companies presented their vehicles individually to customers at home; later, the first locksmith workshops used by private motorists for customer service set up small showrooms, a »Point of Sale« so to speak. Interestingly, national and international sales in their early phase often ran through a few exclusive wholesalers who had secured this contractually and were thus also responsible for high prices.

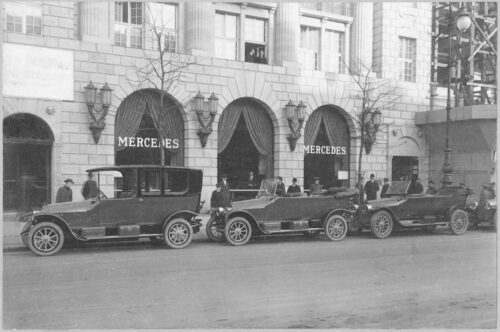

Mercedes Palace in Berlin-Mitte: Exterior view of the elaborately designed branch of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, which opened on September 30, 1913. Exterior view with passers-by, photographed around 1913.

Daimler, for example, could only sell 20 percent of its vehicles itself — in 1913, the manufacturer opened a large branch for this purpose on Berlin’s grand boulevard Unter den Linden, the Mercedes Palace. The sales representatives of the young Mercedes brand certainly did not lack sophistication when they took care of one of the very first car dealerships in the early days of product marketing.

On the one hand, they relied on magnificent architecture and a large sales salon, equipped with curtains and Greek statues, which attracted the wealthy clientele with the slogan »See, buy — drive«. On the other hand, the special quality of stay succeeded in defining a new kind of meeting point for Berlin society — the appeal of the location was further enhanced by the spatial combination with a well-known wine house. Our automotive shift thus seemed to have started successfully.

From the second half of the 1920s, the larger European manufacturers increasingly established their own extensive showrooms in reputable and frequented locations of important major cities. With the advent of modernity, a characteristic marketing and sales culture developed, which quickly shed the representative-conventional style of the early 20th century and aimed to place the automobile as a technical product, and above all as a bearer of a new, namely the »modern« lifestyle, in an authentic setting.

With the slogan »See, buy — drive«, the wealthy clientele was recruited. (Mercedes Palace, Berlin, 1913)

The most architecturally and for the automotive culture of that time certainly most exciting concept was realized by the office of Laprade Bazin in 1929 in Paris for Citroën: The ten-story, 10,000-square-meter Department Store for Cars, located not far from the Champs-Élysées, displayed automobiles as if in a shop, on shelf-like galleries. The foyer was 17 meters high, completely open to the city, thanks to a fully glazed facade. It is understandable that such presentation spaces, along with cleverly designed corporate branding, set standards for the brand’s international dealer network.

The principle of »Brand Spaces« was born and now communicated not only product-specific technicality and modernity but also, with the size of its presentation spaces, corresponded to the significance of a vehicle purchase for the private household. With the first halls or building complexes dedicated exclusively to car sales and potential branch and workshop functions, the consumer-oriented building type of the »car dealership« also established itself in the post-war period. It replaced the previous separation of inner-city sales salons and customer service workshops in the outer districts and offered new opportunities for outdoor advertising and brand self-presentation.

Early examples used the typical industrial and gas station architecture for this purpose, although these differed from other company buildings primarily by the applied signage — the large brand logos or wordmarks along with the corporate colors on signs, facade panels, or flags. Still, the vehicles stood factually isolated in the sales halls. Nevertheless, during the following decades, the emerging and globally popular styles of high-tech architecture and postmodernism led to a significant intensification of the communication capability of buildings and facades.

Undoubtedly, the architectural aesthetic supported the external impact of those »Brand Galleries«, which, from the perspective of engineers and brand managers, correspond to the rapid pace of innovation in automotive technology and should reflect the state of the art of their vehicles both atmospherically and stylistically. For the introduction of a new concept or production site, the accompanying campaign was soon no longer sufficient. It was recognized that special brand architectures, ideally even »signature buildings«, proved particularly valuable in this regard. Not only because they made the new product visible in the clearest way, but also because the »special« could quickly provide effective brand advertising independently via »viral marketing« with the advent of internet communication.

One of these successful eye-catchers was the Smart Tower, which has been placed sixty-five times in Europe in front of a Smart or Mercedes-Benz dealership since 1998. Those glass towers, in which small cars were stacked on thin, elevator-like frames, conveyed not only an impression of lightness but also of unproblematic fun with mobility, which could noticeably lower the access threshold of young urban consumers to the product. They cleverly played with the psychological effect that products in illuminated display cases are perceived as higher quality, and products shown as widely available are perceived as more affordable.

Similarly, the by no means less spectacular, yet gigantic display case of the Mercedes-Center Munich, opened in 2003 as part of the local branch. Its six-story glass facade stages the global brand with countless silver vehicles, arranged like objects on a shelf. A magnificent serial aesthetic in the brand’s traditional corporate color. Who wouldn’t want to at least briefly »drop by Mercedes« after that?

Mercedes-Center, Munich Branch, 2003

One recognizes: The modern car dealership as a building type is a consequence of the insight into the importance of the buying experience. In the mid-nineties, a textbook states: »The process of realizing that the car is no longer the focus of all contacts with the dealership has long begun for customers. He, the customer, will be the human center of all efforts his dealership makes for him.«

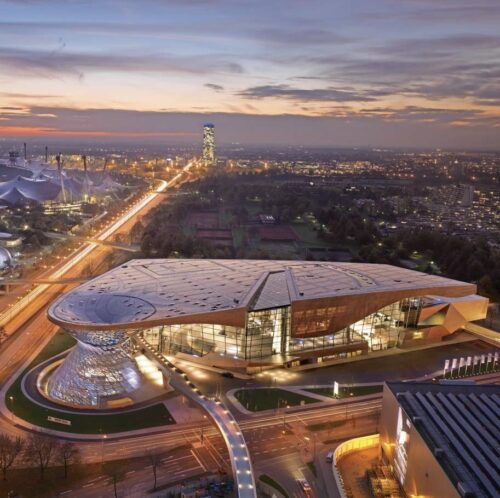

New and redesigns of corresponding branches are geared towards buyers, from operational processes to spatial atmospheres. Not only sales, but also after-sales service and image building need to be managed. The sales halls continue to grow, not only to present even more vehicles from the expanding range, but also because of the emerging concept of event marketing, which demands additional space. Small shops, seating areas, and bistro offerings have long joined the reception desks and glass-enclosed booths for consultations — now, themed islands connected with temporary campaigns and event possibilities are following. The showroom becomes a veritable showplace — almost beyond improvement, Coop Himmelb(l)au’s Munich BMW Welt then entered architectural history in 2007.

BMW Welt, Munich, 2007

A few years later, the next evolutionary step for car dealerships followed — reacting to the general establishment of the latest techniques in information and communication media. The Ingolstadt-based company led the way: In 2012, the first cyberstore concept Audi City opened in exclusive London-Mayfair. Audi combines the real with the possibilities of an extended virtual space on a limited area — due to the expensive inner-city location. A single vehicle is sufficient as a physical contact point with the brand; the presence of the remaining offering of 45 types and versions in one million configurations is managed virtually: Using freestanding multi-touch tables, the virtual vehicles can be configured 1:1 and also moved on large wall screens. The display and the experience shift into the illusionistic representation and the fascination of interactive play. The Audi House of Progress in Autostadt Wolfsburg further developed the concept of the now-closed Audi City in London, thereby setting new standards for the brand’s staging. There, a Table of Vision now presents the latest state of automotive futurology.

Behind the timeless exterior architecture of the Audi Pavilion in Autostadt Wolfsburg, Audi makes the four brand values of digitalization, design, performance, and sustainability tangible for visitors.

The trend of showrooms established in London, which supplemented the usual, decentrally located branches, prevailed in the following years — the urban flagship store became the model, combined with the experiences of successful automotive museums. The VW Group, for example, uses Berlin’s prime location, Unter den Linden, for its DRIVE. Volkswagen Group Forum with exhibitions, conference rooms, and gastronomy. Test drives are also arranged, and the Volkswagen Bank is located next door. Some of the brands displayed ideally match the nobility of the location: Bentley and Bugatti, whose distinctive grilles become ideal attractors in the shop windows. One would have to say, buying a car has never been so cultivated.

Even in 2023, the dynamic of the paradigm shift in mobility has by no means diminished, but it is developing on two tracks. On the one hand, the industry is reducing pure exhibition and sales areas — inner-city shops with a single display vehicle are preferred. Almost 90 percent of interested parties enter the sales room already pre-informed, and 60 percent have already decided on the model and price. Instead of branches and authorized dealers, an agency model is envisioned — like Mercedes-Benz. This manufacturer plans to reduce its showrooms by one-fifth by 2028 — supported by temporary small pop-up stores. At the same time, numerous online shops are already planned for the present.

DRIVE. Volkswagen Group Forum, exhibition »Driven by Dreams. 75 Years of Porsche Sports Cars.«, 2023

Marketing and sales have long expanded their platforms and switched from analog customer conversations to multi- or omnichanneling. All communication channels are served. Instead of the revolving door into the car salon, today the landing page, i.e., the brand’s web presence or its activities in social media channels, primarily takes its place.

On the other hand, there must still be a physical place for analog encounters with the product — the automobile is not yet suffering from habitat loss. Nevertheless, spatial concepts are noticeably changing — and this is the second path of current development, which is primarily based on sophisticated interior architecture and spatial scenography. While the pleasantness of a dignified sales salon originally relied on traditional, luxurious lounge qualities such as armchairs, sofas, displayed magazines, and free drinks, these are now complemented by emotionally designed and quasi-familiar, or at least individually customer-appealing, atmospheres.

The guiding narrative changes depending on the brand and target group — from gentle mall-like strolling to an active-sporty experience like at a Mercedes-AMG Experience Center with racing simulators.

NIO House in West Lake, Hangzhou, China, 2018

Café in the NIO House in Tianjin, China, 2019

For the increased volumes of sales architecture and the significantly higher budget that comes with it, these investments seem justifiable, considering the recently realized locations, especially of the new Chinese premium brands such as the NIO Houses, which are referred to as »Flagship Automotive Gallery and Clubhouse«. Their interior design strives to incorporate surface materials and design language that reflect vehicle design, such as that of a NIO ES8 or EVE, especially since in many areas, no automobiles are deliberately present. Here, Living Rooms and Member Areas and play areas for the children of customers and guests are set up, as if one were in a hotel or a private club. To manage this creatively and at the same time meet the technical demands of the brands, manufacturers commission renowned offices such as Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects or MVRDV. Planning ideas use the motif of a »journey« that one wants to offer visitors: »A succession of layered concatenated spaces organize the different functions and give hierarchy with levels of privacy and connections.«

Anyone who then actually visits such a house and has left the aesthetically cool areas of pure car presentation towards the hotel-like, family-oriented living zones will be overcome by a feeling, depending on the type, either irritating or comforting: How much they have changed, the presentation spaces of our new cars.

What the oil-smelling customer service workshop once directly communicated, namely the technology and the sensory-craft element of driving, is now apparently strictly reconditioned and oriented towards the detached stay in the upholstered and media-dominated living space of the vehicle. It is understandable that the most prominent exhibits in 21st-century car dealerships are precisely those cars that suggest autonomous driving to their new owners.

But for those who think differently, there are still the company branches with their archaic experience spaces, where car-loving customers can authentically pursue their passion, even if one sits in a soft lounge chair and the glass pane pleasantly separates one from the real wrenching work. »Nothing is impossible« — to quote Toyota.

ARTICLE FIRST PUBLISHED IN CHAPTER №VIII »ELEMENTS« — SUMMER 2023