Text by Bettina KRAUSE

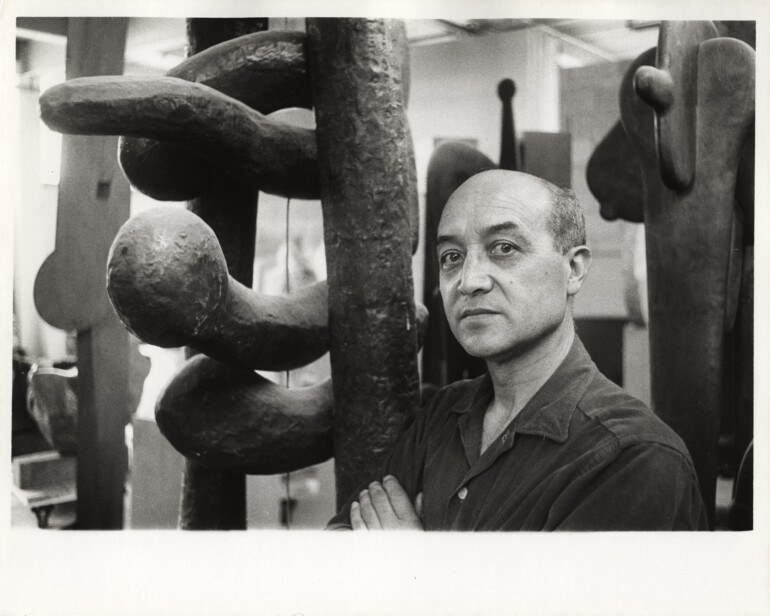

The aesthetic of Isamu Noguchi’s work stands as a remarkable example of timeless artistic expression, with his Japanese-American heritage forming a central part of his oeuvre. Noguchi can be seen as a modernist between two worlds—shaped by cultural heritage yet driven by the search for his own personal and artistic identity. His universal aspirations extended beyond art itself, and the power and influence of his work continue to resonate to this day.

A UNIVERSAL ARTIST

Isamu Noguchi (1904 – 1988), one of the most influential artists and designers of the 20th century, coined the phrase »There is no such thing as time«. In his artistic work, he repeatedly grappled with the question of the timeless form. In addition to sculptures, gardens, furniture, ceramics, he even created architecture and stage designs, using a wide range of materials such as stainless steel, marble, cast iron, wood, bronze, basalt, granite, and water. His works have been shown at documenta in Kassel, at the Venice Art Biennale, and in major museums around the world. As a global citizen, Noguchi traveled throughout his life and was inspired by the purity of Italian marble and contemporary art, as well as by Chinese ink painting and the purist ceramics and traditional gardens of Japan. In his avant-garde work, whether as an artist, designer, stage designer, landscape architect, or sculptor, he combined impressions from East and West, processing the themes of his life.

Sunflower (Himawari), 1952, Shigaraki stone-ware, Sogetsu Foundation, 66 x 35 x 19 cm

BETWEEN NEW YORK AND JAPAN

But how can we imagine Isamu Noguchi as a person? He is often described as having felt lonely, with a persistent sense of not belonging anywhere—a feeling rooted in his childhood. Noguchi’s parents, who both began their careers as writers, were never married. His mother, Léonie Gilmour—an American of Irish descent—was working in New York City as a young writer and editor when she met the Japanese poet Yonejirō Noguchi. Yet only a few months before Isamu was born in Los Angeles on November 17, 1904, his father returned to Japan alone—marking a first rupture, a first abandonment.

The Kite, 1959, Anodized aluminum, 158.1 x 44.8 x 14 cm; The Mirror, 1958, Anodized aluminum, 161.1 x 72.2 x 9.5 cm; Man Walking, 1959, Anodized aluminum, 220.7 x 95.9 x 87 cm

When Noguchi was two years old, his mother moved with him to Japan, but he rarely saw his father. »All I can remember in my early childhood is being a child living with his mother,« Noguchi is said to have remarked. Since his mother worked as an English teacher, the young Noguchi spent much of his time alone, which taught him independence. Another rupture followed when his mother sent him back to the United States alone in the summer of 1918—at only 13 years old—to attend high school in Rolling Prairie and later in La Porte, Indiana. He did not see his mother again for five years. One description of his character aptly notes that this circumstance »added another layer to his increasingly complex identity.« Noguchi resented his mother for sending him to America against his will, and later commented on a visit from her: »My extreme affection never returned, and now, the more maternal she became, the more annoyed I became with her.«

Léonie Gilmour, Mother, c.1932, Terra-cotta, 20.6 x 18.1 x 19.1 cm, Private Collection

ENCOUNTER WITH TIMELESSNESS

Nevertheless, the young Noguchi, who had begun studying medicine in New York City after graduating from high school, followed his mother’s advice and took evening classes in sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School. Had she already recognized her son’s great talent at that time? After only three months at the evening school, Noguchi presented his first exhibition and from then on earned his living by creating portrait busts. One of his first impressive academic works, Undine, a female plaster sculpture, was created in 1926. However, because academic work no longer satisfied him after a short time, Noguchi sought new inspiration and became enthusiastic about modern and contemporary art. In particular, the works of the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, which he had seen at a New York exhibition in 1926, impressed Noguchi so deeply that they fundamentally changed his artistic direction. He was said to have been spellbound by Brâncuși’s vision and work. With his minimalist sculptures, which he refined again and again in pursuit of the essence of things, Brâncuși strove to create something both modern and archaic—ultimately, something timeless.

Man (Otoko), 1952, Bizen stoneware, 55.6 x 16.5 x 15.2 cm, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York

THE ESSENCE OF NATURE

Fascinated by this idea, Noguchi seized the opportunity in 1927 to travel to Paris on a Guggenheim scholarship. There he worked for five months in Brâncuși’s studio as an assistant and was inspired by the simplicity of his designs. »What Brâncuși does with a bird or the Japanese with a garden is to take the essence of nature and distill it. Just like a poet does. And that’s what interests me. To get to the heart of the most important forms in a poetic translation,« said Noguchi. Inspired by Brâncuși’s forms and philosophy, Noguchi turned to modernism and abstraction, and from then on imbued his own works with lyrical and emotional expressiveness, an aura of mystery. In works such as Man (1952) or in the exhibition of his marble sculptures at the Stable Gallery in New York in 1959—considered a tribute to Brâncuși—the influence of his mentor is especially evident. Again and again, Noguchi’s origins played a role in his life; as someone who was half American and half Japanese, he often faced prejudice. Thus, influences from both East and West, along with questions of identity and belonging, came to shape his art.

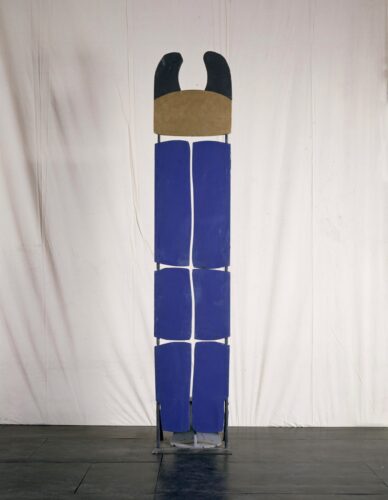

For Martha Graham’s Hérodiade, 1944, Plywood, paint, 246.7 x 90.8 x 69.2 cm, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, gift of the J. M. Kaplan Fund, 2002

CARVED IN STONE

After extensive travels through Asia, Mexico, and Europe, Noguchi returned to New York City in the early 1930s. In his Greenwich Village studio, he devoted himself to a wide range of design projects alongside his portrait sculptures—designing landscapes, playgrounds, and large-scale stone works, while also exploring new materials and methods. His art reflects the sensibilities of an era shaped by the upheavals of World War II. During this time, he created striking sculptures inspired by archaic Greek figures, which were presented in the 1946 exhibition Fourteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Of these sculptures Noguchi said that they defy gravity, just as they defy time and even life itself, which could be lost at any moment. Time—and the attempt to transcend it through the essence of form—remained a recurring motif throughout his work.

Fourteen Americans, Museum of Modern Art, September 10 — December 8, 1946

ARTISTS AND DESIGNERS

Even though Isamu Noguchi is often regarded as a »designer« today, his self-image was fundamentally different: »I decided to just be an artist,« he once said of himself. In his practice, Noguchi consistently collaborated with artists from a wide range of disciplines. For example, beginning in 1935 he created stage designs for Martha Graham, worked with her throughout his life, and drew lasting inspiration from their collaboration.

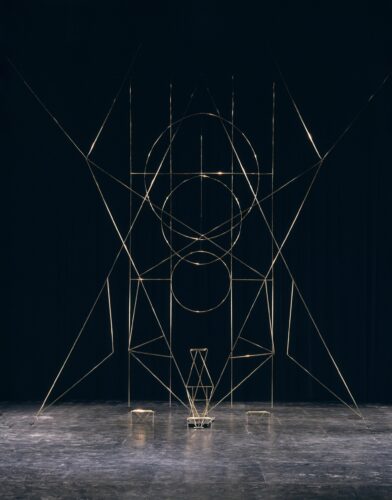

Center Elevation for Martha Graham’s Seraphic Dialogue, 1955, Brass rods, steel cable, 671.8 x 518.1 cm

Gate of Hippolytus for Martha Graham’s Phaedra, 1962, Paint, canvas, wood, metal, 307.3 x 68.6 x 38.1 cm

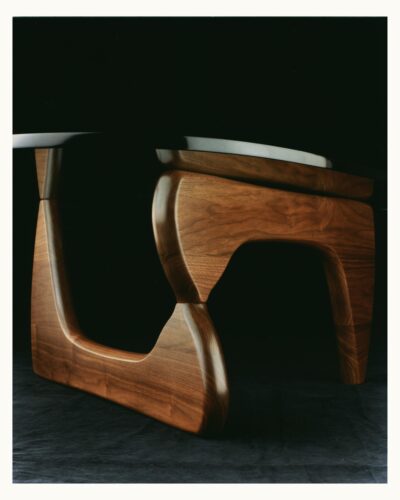

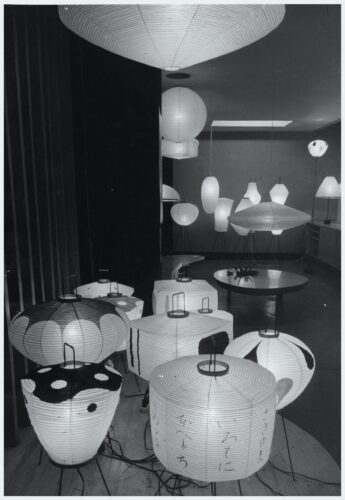

Through his stage work, Noguchi realized that he wanted to create sculptures for space itself, and from then on he also devoted himself to furniture design—most notably his famous Coffee Table of 1944. In the 1950s he created the first Akari lamps, crafted from mulberry paper and bamboo. Even though many of his objects were later produced in large numbers, he still considered them works of art. Noguchi drew no distinction between his artistic practice and commercial design—if the opportunity arose to bring a design into mass production, he embraced it. In 1937, for example, he designed an intercom for the Zenith Radio Corporation, and both his Coffee Table and his Akari light sculptures are still in production today.

Originally manufactured for the American furniture manufacturer Herman Miller, the Coffee Table from 1944 is still produced today.

Akari Lamps, Chuo Koron Gallery, August 2 – 7, 1954

HIS UNDERSTANDING OF TIME

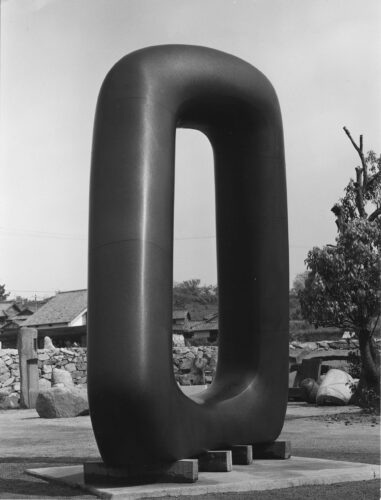

Although Isamu Noguchi was not opposed to mass production, he often found its limits. In an interview, he summed up this problem while also offering an insight into his understanding of time: »If you want to live and work in an industrialized world, you have to use industrial materials and tools. However, I was not entirely satisfied with this, because I felt that the limitations of such tools force you to be part of the industry instead of being free. And I felt that the more old-fashioned way of doing things, for example with stone and with your own hands, leaves a way to freedom. And so I went back to the stone. I also worked with wood for a while, but I switched back and forth. Sometimes I feel like I’m part of today’s world, but sometimes I feel like I might belong to history or prehistory. Or that there is no such thing as time. But if you are trapped in time, in the immediate present, then the selection is very limited. You can only really do certain things right that belong to that time. But if you want to break out of this time-boundness, then the whole world you see—not just the industrialized world—is the place where you belong.«

Energy Void, 1972–73, Swedish granite, 361.6 x 31.1 x 112.4 cm

WHAT REMAINS

Noguchi’s legacy is immense, due in part to the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum (today known as The Noguchi Museum) in Queens, New York, which he himself initiated and opened in 1985. He designed the museum in a 1920s industrial building located directly across from his studio. Alongside photographs, drawings, and models, visitors can experience his sculptures in a serene garden setting. Noguchi also stipulated that his studio in Mure, Japan, be preserved to inspire future artists and scholars — a wish realized with the opening of the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan in 1999. For him, both his work and his museums were to be understood as a crossroads where East and West meet. Isamu Noguchi passed away on December 30, 1988, in New York. Through his diverse artistic practice, he succeeded in uniting Western and Eastern cultures — creating objects that transcend their time. He may have had this in mind when he remarked: »A museum is an archive, a depot against time. It has a touch of eternity.«

FIRST PUBLISHED IN CHAPTER №V »TIME AND SPACE« — Winter 2021