TEXT LUTZ FÜGENER

Can design today still learn from the Bauhaus? For all other areas of product and industrial design, this question seems rhetorical. In the case of automotive design, however, it is not. With a few exceptions, there is no history worth mentioning in which automotive design and Bauhaus appear in the same sentence. Where does this aversion come from and is it time to give it up?

Although the era of modernism has now been part of cultural history for almost half a century, the ideas and work of the Bauhaus protagonists still have an impact on design practice in the broad fields of architecture and everything that is summarized under the terms industrial and product design. More than 100 years ago, the Bauhaus began to devise creative solutions for the enormous tasks that the project of industrialization presented to the world at that time. As long as this industrialization continues in its evolutionary stages, the Bauhaus approaches are at least worth taking up from time to time in order to test their usefulness in specific cases. The Bauhaus was too early to deal with the demands of digitalization, but even in the digital age, people still live in houses and use physical objects. And as long as this does not change fundamentally, approaches in this regard will lose little of their relevance. The Bauhaus still has the potential to be a guide and quality benchmark for design concepts and achievements and––well––to lend them intellectual brilliance. There is a great temptation to see the strong Bauhaus brand as a stylistically reproducible design and to project the designs of artifacts that still seem modern today onto new products.

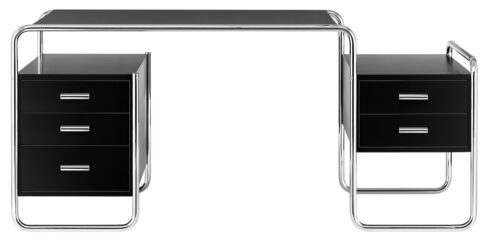

Thonet, Tubular steel desk S 285, 1935

In today’s era of marketing primacy, a brand as strong as the Bauhaus is simply too much of a lure. The often invoked Bauhaus style does not exist, but the Bauhaus code certainly does. For some, it is indeed too powerful! The New York architecture critic Mark Wigley even calls for the world to be liberated from the ideas of the Bauhaus. He suspects the representatives of the Bauhaus movement of having aimed for a perfect human being (super human) and believes that we are all still victims of the Bauhaus and its encroaching optimization efforts today. He speaks of the Bauhaus virus––a powerful metaphor in post-corona times. It is therefore all the more astonishing that the supposedly viral Bauhaus code was hardly able to develop any influence in a special design field––that of vehicles. Automotive design and Bauhaus behave like immiscible liquids. Although there are occasional efforts to whisk them together, the separating layer always forms by itself.

Walter and Ise Gropius with their mutual friend Lily Hildebrandt: Photographed by Walter Gropius with a self-timer during a car trip with their new, white Adler Standard 8 in Dessau, 1930.

In order to explain this rejection phenomenon, it is probably necessary to investigate various causes. The first is obvious: Vehicles were not one of the original fields of work of the Bauhaus during its active period between the world wars, nor did any of the former Bauhaus members scattered around the world favor this topic in their active years afterwards. However, as with almost every rule, there are exceptions––albeit few. The first was Walter Gropius’ design work for the Frankfurt automobile brand Adler, which was important before the Second World War. Familiar with each other through Gropius’ design work on the brand’s appearance, the collaboration continued with the design of special bodies for the Standard 6 and 8 models––both luxurious models and thus created more in the spirit of a Wilhelm Wagenfeld than a Hannes Meyer. Gropius certainly created something new in terms of aesthetics and detail. A driver’s door that could be hinged either at the front or rear, as in the Standard 8 convertible, would still be an eye-catcher today, and the idea of reclining seats in the Standard 6 saloon has even become a common feature of the automobile. However, the limits of the framework set by the manufacturer did not allow Gropius to question the structure of the automobile with the radicalism he was familiar with from his work as an architect. Disruptive approaches to the automobile of the future were coming from other directions at the time. Gropius himself was obviously satisfied with the results of this cooperation and drove one of the few vehicles produced––an Adler Standard 8 Cabriolet––as his private car until his emigration in 1932. Unfortunately, none of the few examples sold survived the following world war and it remains questionable whether they would otherwise have been part of the physical, but even more so the mental, history of the Bauhaus today and thus would have claimed the theme of automobile design for it. Probably not.

The Junkers G 38 (1929) was the largest land plane of its time and was considered a marvel of engineering. With a wingspan of around 45 meters and a wing area of almost 300 square meters, the aircraft was far larger than the usual proportions of the time and was only comparable in size to the Dornier Do X seaplane.

Its collaboration with the aircraft manufacturer Hugo Junkers, also based in Dessau, is exciting because it is much more interwoven with the activities and habitus of the Bauhaus. Although this did not focus on the field of mobility, it was thematically influenced by its new requirements. The now world-famous claim »Form Follows Function« resulted not least from precisely this type of networked approach to design and technical development that was implemented here. For its pioneering work in the development of passenger aircraft, Junkers needed innovators who were willing and able to act independently of established conventions. In the 1920s, passenger aviation was naturally elitist and reserved for the luxury-conscious upper class. When designing the interiors of the aircraft, the requirements of the aircraft developers for lightweight construction and stability were diametrically opposed to the usual images of a luxurious interior. The radically new aluminum furniture designed and manufactured at the Bauhaus created a new, modern image of high-quality design with its high-tech design. The congenial collaboration between Junkers and Bauhaus not only had an impact on the furniture industry, but also sowed the seeds for a globally effective counter-image to the opulence of traditional luxury, which was able to establish itself at least as an alternative in almost all fields of design––with the exception of the automobile. To this day, two traditional vectors must be observed in order to exert luxury: Performance and massive ostentation in the broader sense. Often in combination.

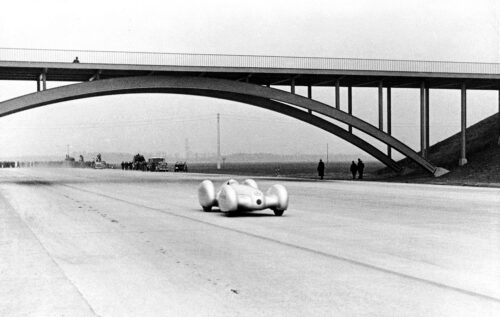

One of several Junkers structural steel bridges on the Dessau autobahn world record track, which the racing driver Rudolf Caracciola drove through in a Mercedes W 154 on the day of its inauguration in 1939, setting a new record time.

The second reason is the fundamental contrast between the approaches of the Bauhaus and contemporary automotive design in the mid-twenties of the last century. While concepts of social building, housing and living were put into practice in Dessau, on the other side of the Atlantic the still young discipline of automotive design was subject to the laws of marketing as part of the mass motorization of the USA. After GMC boss Alfred P. Sloan’s simple but effective basic idea for utilizing the possibilities of design had relegated the previously unchallenged market-dominating Henry Ford to the back of the pack in just four years, the design of vehicles seemed solely committed to market success. Although the Bauhaus was also open to cooperation with industry and carried out a large number of small and large projects, it saw itself as an equal partner and never as a means of maximizing profits in a world of products. From today’s perspective, the automotive industry in the USA could be said to have been far ahead of its time. It simply skipped the era of modernity and created the postmodern product half a century earlier than the rest of the world. Automobile design thus became a kind of counter-design to modernism. The rapidly growing influence of the US car industry after the Second World War and the associated export of its ways of thinking and working initiated a competition between design philosophies. And the more saturated the markets became and the more cut-throat competition raged on the markets, the greater the number of defectors became. The transition from the era of modernism to postmodernism can also be understood as a reversal of precisely this relationship in favor of the market-oriented orientation of design à la Sloan.

Fiat Panda, 1980-1984

There are indeed automobiles whose design could have invoked the Bauhaus code in all consistency: The Fiat Panda, designed by Giorgio Giugiaro and released in 1980, would even stand up to the strict, socially minded standards of Hannes Meyer. The constraints for the design of this Italian people’s car were extremely tight––even the number of spot welds to be used in the production of the body was specified and strictly limited. The design is stringent, economical, aesthetically mastered, modern and logical, and as a superlative of automotive design it is certainly to be rated higher than numerous spectacular works à la ISO Grifo or Bugatti EB 112 from the same pen. Of course, Giorgio Giugiaro does not need Bauhaus glamour––after all, his name itself stands for one of the strongest brands in the history of automotive design. It is not known to what extent he was impressed or influenced by the Bauhaus. The design of the Panda, with its offensive pragmatism that seems almost vulgar to the apologists of automotive aesthetics, has many a critic in a quandary. A »household appliance on wheels« or an industrial design are common interpretations for resolving the inner conflict. You simply put the Panda in a different drawer and all is right with the world again.

Exporter 2 – portable radio designed by Otl Aicher for BRAUN, 1956.

The rift also runs through the fronts. In 1984, the important German graphic designer Otl Aicher––himself unquestionably a member of the classic-modern Bauhaus tradition of the Ulm School––published a book entitled »Kritik am Auto. Difficult defense of the automobile against its worshippers«. Today, the book reads at times like self-therapy, which is archetypal for the inner conflict of the protagonists of modernism in design, but also for today’s discourse on the subject of the car. As aptly as one formulated the misguided development of the contemporary automobile as a means of transportation on a rational and analytical level, one had succumbed emotionally to the allure of the subject and had to be counted among the »worshippers«. Aicher celebrates the compact Fiat Uno and––himself an enthusiastic sports car driver––reproaches the Porsche 911 for its »styling«––in modernist circles a fighting term for lack of concept and superficiality. However, from today’s perspective, his equally critical assessment »er fährt auch, wenn er steht«, marks nothing less than an almost self-evident minimum requirement of contemporary automobile design.

There is nothing to be said against a commitment to Bauhaus in automotive design––not as a universal formula, but as a pre-formulated demand for functional innovation and aesthetic clarity. The Bauhaus code, which is sometimes overused elsewhere, could be an inspiration of untouched charm for the automobile of the future. It would be worth a try. Mr. Wigley would probably have to take the train to be spared the Bauhaus virus.

ARTICLE PUBLISHED FOR THE FIRST TIME IN CHAPTER №VIII »ELEMENTS« — SOMMEr 2023