TEXT ANDREAS K. VETTER

It would actually be much more exciting to deal with what happens than with what is. Because that is immediately recognizable, static, defined. In contrast, our world and things are constantly moving and changing. Ancient Greece called this »metamorphosis« – and that’s what we’re talking about here.

»Lost in Translation«––who hasn’t seen the classic film starring Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson, in which two people who don’t know each other meet by chance in Tokyo, a Japanese megacity that is unfathomable and untranslatable for them, which is presumably why they have sought it out. However, the intense feeling of being lost gives their encounter a common level on which they meet, talk and live as if in an intermediate world––for a few days. Watching the film, you enjoy entering this floating state with the two of them––light, open, liberated. You wish you had the courage or the sovereignty to be in-between, as the foreign metropolis allows the main characters in the film to do. Perhaps because it is something subconsciously important to our existence that we repeatedly suppress out of reason or convenience: an interim state of mind that applies to all people in the most diverse life situations and is typical of processes, evolutions and formations. It is the moment of change––sometimes short-lived, sometimes with a noticeable duration––that is expressed quite well in the concept of hovering. The Swiss artist couple Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinger achieved a congenial visualization of such a process with their touching »Giardino calante« installation at the 2003 Venice Biennale: in the nave of the church of San Staë, people move under a three-dimensional sphere of flowers and delicate natural elements that seem to fall down from the vault without reaching you directly. The beauty and vitality of what was otherwise painted on the ceiling as floral decoration in the Baroque period and stands for creation becomes physical and moving. This brings us closer to the miracle of the speaking church interior; we find ourselves, as it were, in the process of creation, from the ideal budding to the fullness of nature.

Gerda Steiner & Jörg Lenzlinger, »Giardino calante« (installation), Church of San Staë, Biennale 2003, Venice

While the flanking states––i.e. the initial situation on the one hand and the new on the other––are tangible for us, as they can be clearly defined and also clearly perceived due to their stability, the in-between is a phenomenon whose nature and form is too fluid to »have a handle on«. Time and again, people are forced to accept this period of transformation, whereby they are confronted with it in the most diverse dimensions of life. Sometimes dreams revolve around those motifs of tense pauses, as we are dealing here with the most intense moments of our experience of the world––perhaps Paul Virilio’s famous formula of »frenzied standstill« fits quite well here? Ultimately, however, nature is behind all movement––from the cosmic to our planet. On the constantly rotating earth, vitality and life are defined by the movement and transformation of states: emergence, growth and decline. Symbols of this are the bud or the larva that develops into a butterfly––and this without being able to see the beautiful final stage of the original form, even if it is already within it. Reflections of this omnipresent metamorphosis, as this phenomenon of shape-shifting was called in ancient Greece, can be found in the culture that humans developed as a living being typical of their species from the earliest epochs of history.

wiki/File:Marina_Abramović,_The_Artist_is_Present,_2010_(2).jpg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

Marina Abramović, »The Artist is Present«, MoMA New York, 2010

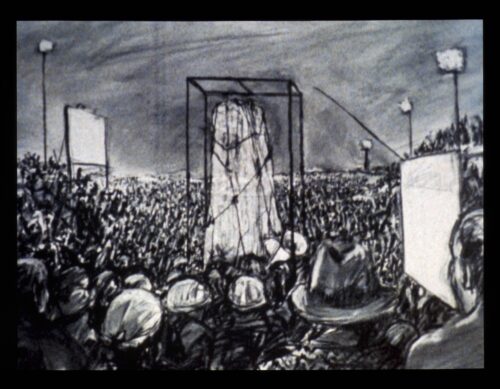

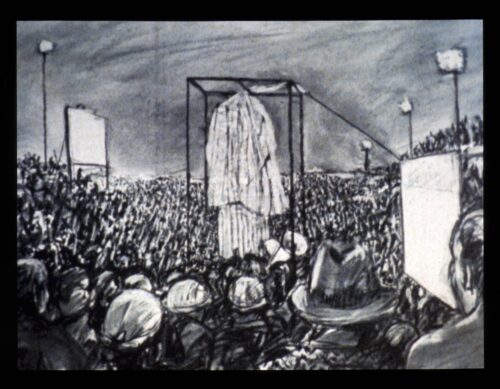

So it’s no wonder that, alongside philosophy, art is also interested in those slow-motion tipping points, those short periods of time in which one situation leads to the next. Impressive examples are easy to find: For his Florentine sculpture from the story of David, Michelangelo chooses exactly the minute in which the boy develops the courage to hurl the stone he is weighing in his hand at the giant Goliath; Marina Abramović’s performances lead those present into an uncomfortable situation, forcing them to constantly resist the pressure to avoid the exhausting or upsetting confrontation with the art action––only those who can stand the artist sitting in front of them in silence for hours, for example, will ultimately take part. The South African William Kentridge could also be mentioned with his animated films, mostly drawn in charcoal. When you see them, you can’t take your eyes off them, because unlike conventional films with separate individual images, you experience the process of change and the traces of what has gone before always remain at least briefly present in the current film still. »In this way, each sequence carries the story of its development within it. What the technology itself brings with it is a sense of time«, according to the artist. The cases listed demonstrate the intention of art to really and tangibly bring the recipients into its sphere––by subversively placing them in a precarious situation. A routine or emotionally protective perception is not possible in this way. Instead, one must surrender oneself to the experience of this ambivalent situation.

William Kentridge, »Monument« (Stills), 1990

But why is this so fascinating? Human beings actually strive for order, which in a practical and cognitive sense would only give life a before and after. Immediately before the introduction of change and also in between, there is ambivalence, hesitation and dithering about changing a safe situation, the fear of an uncertain outcome––and that is unpleasant at first. That’s why we analyze and plan wherever possible so that everything runs smoothly and the results don’t come as a surprise or create unforeseeable problems. However, transitions are fundamentally unavoidable in an organic, metabolic system in which we live. The nature of the matter always includes its ability to change, even the certain change of what we are currently experiencing. And humanity has always reacted to this: In archaic societies, for example, initiation and sanctification rituals arose in which a specific period of time, a symbolic act and special objects performatively accompany the transition into a new quality, such as the admission of young men into the circle of adults. The ancient Egyptian cult of the sun god Ra worked with the barque as a real embodiment of his journey across the sky and through the underworld. People celebrated this in processions in which a Nile barge charged with a mystical aura was moved from the water to the holy place. Christian theology also had to grapple with the zone between secular reality and the sacred sphere. It developed the concept of limbo––a non-real waiting room for the souls for the temporally unmeasurable but unimaginable intermediate state until redemption.

Norman Foster, Reichstag Dome Berlin, 1999

In factual life on earth, on the other hand, which is constantly and often inexplicably changing, cultic and individual rituals give people more time and sensory influences to empathize and understand––which is why sacred places such as altars or graves have been circled since time immemorial. Turning around something makes you think, see more sides, experience a small effect of the endless in the circular movement, which is typical of the permanent mobility of the cosmos. In this respect, it is not only children who love walking around in circles, adults also enjoy the formal constraint of a circular path, especially when, as with a spiral, the perspective changes subtly with every step. Norman Foster’s architectural concept, who was commissioned to redesign the dome above the Reichstag in Berlin in 1995, also operates with a complex implementation of this motif. Visitors not only walk upwards in a spiral movement along the edge of the transparent roof structure, where they can look out over the country, which is governed from within the building. They can also look down into the plenary chamber and watch their deputies making their case and taking decisions. The discursive process of the legislature is reflected in the movement of the citizens in the iconically towering dome and thus becomes conscious in the performative movement of all.

Refik Anadol Studio for Bvlgari, Milan: »Serpenti Metamorphosis« (installation), 2021

The project »Serpenti Metamorphosis« by media artist Refik Anadol does not use architecture, but visual effects to address the motif discussed here. The large spatial installation, realized in Milan in 2021, creates wall-filling, constantly reconfiguring surfaces that are composed of 200 million varying images of nature in 3D and are connected to animal protagonists––snakes. These are generated by an immersive computer program: »… as poetic imagery mimicking natural transformations and snakes that seemed to slither and change throughout the installation«. Anadol has a concrete goal: »I welcome the machine as a collaborator, it allows me to make the invisible visible. Metamorphosis is really the perfect symbol to represent overarching ideas of evolution, growth, and precision in the world that surrounds us.« The use of AI also makes it possible, depending on the situation, to emit a fragrance that makes the experience synaesthetic. The phenomenon of permanent change in nature is transformed into an equally volatile visualization, which in turn has an emotional effect and changes through the reactive actions of the audience within it.

Rei Naito, »Matrix«, permanent installation Teshima Art Museum, 2010

While Anadol’s media installation is in principle an artificial setting, in another artistic work nature actually appears as an active player and can thus be experienced in its metabolic movement. The Japanese artist Rei Naito worked on the floor of a specially constructed grotto-like concrete architecture––the Teshima Art Museum––using a special surface shape and punctured holes so that the natural spring water in the area forces its way up onto the artificial surface in small drops, which then move freely: »Following the inclination of the floor they seem to race, overtaking each other and occasionally colliding and combining in larger puddles. Dancing in unexpected patterns, they finally gather and are drained through other holes. This splendid movement makes the water look lively, and not only a source of life but alive itself.« Unlike when looking at a stream or lake, the water is not perceived as an element of the landscape, but as a visible and tangible indicator of the vital force of nature, of pushing and becoming––experiencing the process of life, the seemingly eternal cycle of the creation and decay of natural forms in the forming and draining of these small ponds. »Is there anything more moving than this moment of transformation?«, the artist asks rhetorically.

The young Berlin CGI studio PALAM is also exploring this fascinating phenomenon, skillfully bringing it into the reality-based sphere of the product world alongside artistic aspects. Their immersive installation »Metamorphosis« (from page 80), which took nine months to create, gains its appeal not only through a strong aesthetic characterized by intense orange tones, but also through the visionary power of computer-generated imagery. The magical presence of the automotive object is created in a technoid setting, on an active »stage«, which is geared towards both production and presentation and plays on this with its robotic moves: »The stage becomes a canvas where the fluidity of life is explored, offering an intellectual and sensory journey that captures the essence of transformative beauty.« In terms of product design, it is therefore not about a design as the form generated from a material through a transformation process, regardless of whether this is created in a controlled manner as in an assembly, printing or casting process. Ultimately, this thematizes nothing other than the end product. The virulence of the process, i.e. the transformation process itself, and the fact that this metamorphosis is part of the concept and remains present in the form, is much more interesting than the path and period of production.

After all this, what is the conclusion of these considerations, what is the latent and explicit message of these impressive projects and works of art? At any rate, it is based on the insight that the impression that something is standing still is often based on imagination or misinterpretation––although at the same time it is also a cognitive strategy of our brain, which knows that we need a certain order and structure in our analysis of the environment in order to be able to perceive something in peace. This is perfectly fine as long as we have such talented creatives around us, who––like Rei Naito or Anadol––are able to combine the visual, emotional and ultimately also intellectual floating of changing states into wonderful and enlightening spaces of experience.

ARTICLE FIRST PUBLISHED IN CHAPTER №X »STATE OF THE ART« — SUMMER 2023/24