Text by Sarah WETZLMAYR | published in »WORK IN PROGRESS« – WINTER 2023/24

Greta Magnusson Grossman’s footprint in the history of American mid-century design should actually be clearly defined and of impressive depth. It is therefore all the more astonishing that the Swedish-born designer, who emigrated to the USA with her husband in 1940 and caused a sensation there shortly after her arrival, was never really recognized as one of those designers who helped write the design and architectural history of the 20th century with a clear signature. Instead of clear footprints: tiny footnotes. However, if you embark on a search for clues, which is not always easy, you will discover the unique work of a far-sighted pioneer.

In 1906, Greta M. Grossman—then still Greta Magnusson—was born into a family of carpenters in the south of Sweden. The house she grew up in was built by her grandfather himself. Before studying at the renowned design and art academy Konstfack in Stockholm, she tried to continue this tradition and began training as a carpenter. Even decades later, she would always talk about how deeply rooted she felt in the craftsmanship of her parents’ and grandparents’ generation. »I have wood in my soul,« she once said in an interview with the American magazine House & Garden.

At the age of just 27, Grossman was the first woman ever to be awarded the prize for »Good Furniture Design« by the Swedish Society for Industrial Design, and she also decided to study architecture after attending Konstfack. In the meantime, she applied to join the design team of a well-known Swedish department store and was promptly rejected. The reason given was that they had no rooms for women. Grossman’s graduation, a travel scholarship that took her to Vienna, among other places, in 1931, and her start as a professional designer coincided ideally with the growing international interest in Swedish design. »The world will look up to Sweden as the supreme exponent of Modernism which has succeeded in finding its own soul and embellishing itself with a purely mechanistic grace«, declared the journalist and architecture critic Morton Shand on the occasion of the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, which was extremely successful with around four million visitors.

SWEDISH DESIGN IN CALIFORNIA

In 1940, the designer and architect emigrated to the USA with her husband, the jazz musician Billy Grossman. As Billy Grossman was of Jewish origin and Sweden proclaimed neutrality to the outside world but maintained close economic ties with the Third Reich, the couple no longer felt safe in their home country. They traveled by plane and train through the Soviet Union, went by ship to Japan and then by ocean liner to San Francisco, where they arrived on July 27, 1940.

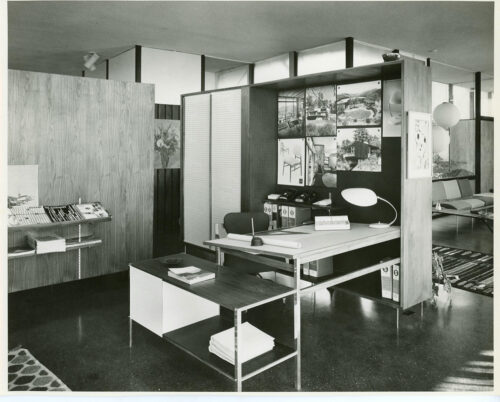

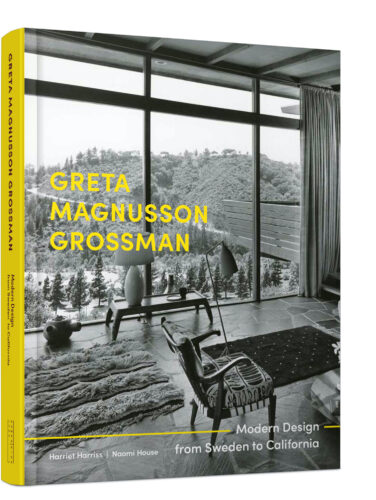

Interior view of Greta M. Grossman’s house on Claircrest Drive in Beverly Hills, 1956-57

She opened her first own store studio shortly after her arrival, where she showed her own designs as well as products by other Scandinavian designers, and set up shop on the world-famous Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles. Once she had built up a customer base and felt she had arrived on the Californian design scene, she decided to move her studio from the posh address to a more affordable location on North Highland Avenue in Hollywood. Her statement that she didn’t need much more than »a car and some shorts« for her new start in the USA not only became the title of a comprehensive retrospective in Stockholm (2010), but also allows conclusions to be drawn about her design philosophy. »Filling every inch of the room with furniture may seem to avoid wasted space—until you find much cannot be used anyway«, she explained with her typical clarity of expression in a 1949 interview with the LA Times. In 1945, she summed up her desire for simplicity: »Simplicity must be the keynote today in any development of the pattern of living. We cannot live in the Victorian style of yesteryear and expect to survive the pressures that go with modern life. We need to free ourselves from all décor that may hamper our outlook, if not our actions.«

Her thoughts on contemporary design were always characterized by a strong claim to functionality, which she occasionally added with a wink. In an interview with American Artist magazine, she pointed out the influence of the fact that most homeowners have to get by without employees. »So, the modern architect and designer must provide average modern housekeepers with an environment that can be kept clean without a retinue of butlers and maids… She requires simple, polished surfaces on her tables, chests, etc. No intricate carvings please, says the modern housekeeper who does her own work.« In theory, this left women, who were still much more stuck in the corset of traditional roles than they are today, more time to deal with things that were less about housework and more about self-fulfilment. Today, one could therefore say that this statement already contained a gently flickering feminist train of thought.

Coffee table Ironing Board, manufactured by Glenn of California, 1954

The success of her work was not long in coming, partly because the aesthetics of European modernism were at the top of the popularity scale in the USA at the time. In 1939, a year before her arrival, the Swedish pavilion at the New York World’s Fair had already attracted a great deal of attention. The architecture critic Lewis Mumford described it in the New Yorker as a »miracle of elegant simplicity«. According to the former director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and the Drawing Center Brett Littman, Grossman’s designs and her studio succeeded in merging Scandinavian Good Design with the American ideal of a Casual Lifestyle. »The Scandinavian Good Design movement really comes out of social thinking, about good design for people—we should make beautiful objects that are affordable, that people can put in their homes,« says Littman and continues: »The American modernist movement also has some of those same ideas, but maybe a little bit less of the kind of social democracy concept behind it.«

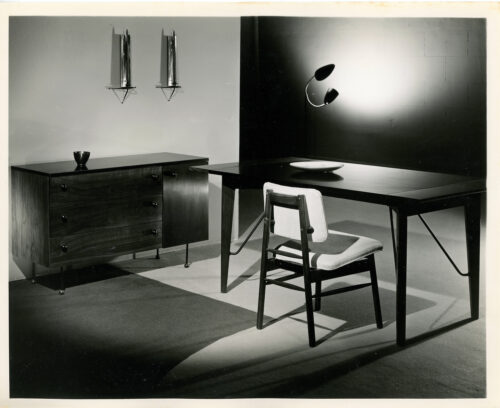

Scandinavian Good Design: Grossman’s designs, produced by Glenn of California, 1952

It wasn’t long before artists such as Frank Sinatra, Greta Garbo, Ingrid Bergman, Gracie Allen and Joan Fontaine were coming and going at Greta M. Grossman’s. She also managed to secure deals with well-known furniture companies such as Barker Brothers, Modern Line, Glenn of California and Sherman Bertram. Her work has also been shown in group exhibitions with other sought-after designers. Grossman was also known for her lavish parties and her networking skills.

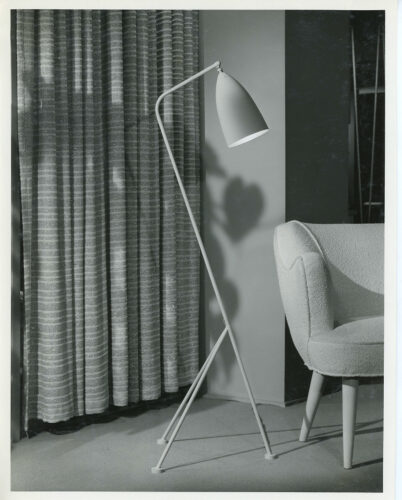

COBRA AND GRASSHOPPER

During her early years in the USA, Greta M. Grossman initially concentrated on furniture and lighting design. Her designs always corresponded to the modern Scandinavian design language that American design enthusiasts were craving at the time, but at the same time always had a spark of stubbornness. The clearly recognizable influence of Mies van der Rohe and other Bauhaus artists did nothing to change the fundamental independence of her objects, the most famous of which include the two lamps Gräshoppa (1948) and Cobra (1949). The simplicity of her designs was also accompanied by a preference for technical sophistication, which can possibly be traced back to Grossman’s beginnings as a cabinetmaker. Some of their luminaires have flexible necks and swivel ball pins on the lampshades.

Gräshoppa lamp, produced by Ralph O. Smith, 1947-48

Unlike her luminaires, which can be adjusted in various ways, Grossman always remained true to her own stance. She countered the prevailing assumption at the time that women could not be assigned mechanically complex tasks, for example, in the following way: »The old idea that women are not as good as men at mechanical work is stuff and nonsense,« Grossman wrote in an issue of the American Artist Magazine. »The only advantage a man has in furniture designing is his greater physical strength.« The design of the furniture produced to this day Gräshoppa also suggests that Greta M. Grossman approached her profession with a sense of humor.

In 1952, Grossman designed a famous furniture series for Glenn of California, which she called the 62 Series because she was convinced that the series of tables and chests of drawers was easily ten years ahead of its time. The 62 Series is one of the designer and architect’s best-known designs. »What I like about her work is the kind of simplicity of it, the sophistication of the engineering, and aesthetically, sometimes they can kind of just disappear into the landscape of your apartment,« Littman notes. »They don’t necessarily call a lot of attention to themselves, but they’re all very functional and useful.«

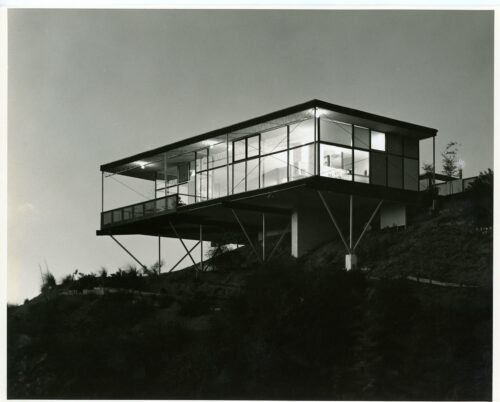

Grossman’s architectural designs were mostly realized on structurally complicated hillside plots;

Claircrest Drive, Beverly Hills, 1956-57

At the end of the 1940s, Greta M. Grossman began to devote herself increasingly to architecture. Around 14 small houses were built in and around LA. Many of these houses, which were mostly built on structurally complicated hillside plots and of which only a few remain today, can be seen as harbingers of today’s Tiny House movement, as they were characterized by built-in features, multi-purpose rooms and numerous multifunctional interior and exterior designs. As an architect, she believed that a home should be a place of refuge and happiness, not a place to flee from. At least that’s how she summed it up in an interview with the LA Times.

MARGINAL FIGURE DESPITE REVIVAL

In 1966, Greta M. Grossman moved with her husband to Encinitas near San Diego and thus withdrew from the design scene. While she devoted herself to landscape painting, her work was increasingly forgotten. Even before her move, she repeatedly expressed disillusionment when it came to the world of architecture and furniture and product design. She said: »We have lost our searching for design that fits the time we are living in. And our design does not start from within, it starts from without. Current design is not thought through and it is not original.« Billy Grossman died in 1978, Greta M. Grossman 20 years later.

Today, Grossman’s designs are being reissued by Danish furniture manufacturer GUBI:

Gräshoppa table lamp, 2013

Gräshoppa floor lamps, 2011

62 Chest of drawers from the 62 Series, 2012

In 2012, her work experienced a small renaissance when Danish manufacturer GUBI decided to reissue some of her most iconic designs. These include the aforementioned 62 Series and the two luminaires Cobra and Gräshoppa. In the same year, one of her aluminum and brass lamps was sold at auction for 37,500 pounds. This small wave of attention did not, however, wash Greta Magnusson Grossman back into the design canon. Although she was the only female designer and architect to even run her own architecture and design studio at a time when the design and architecture scene was populated by only a handful of women, she was not declared an icon after her withdrawal from the world of design, but rather marginalized. In an article published in the magazine Art Papers essay published in 2013, author Arianna Schioldager poses the question that naturally arises: »Why has design pioneer Greta Magnusson Grossman so long remained a footnote in the annals of mid-century modern history, even in the midst of her own revival?«

Harriet Harriss & Naomi House: »Greta Magnusson Grossman. Modern Design from Sweden to California«.

Lund Humphries, 2021

In their essay »Greta Magnusson Grossman: Living in a modern way«, Harriet Harriss and Naomi House propose the following explanatory approach, among others: »In its very principles, modernism established a clear distinction between home and work, the private and the public—and so there is palpable discomfort in the non-binary position presented by professional women who occupy both spheres.« In addition, other—usually structurally anchored—factors also played a decisive role in the struggle for visibility, representation and recognition. Greta M. Grossman, who likes to dance at several weddings (and parties) and has already attended the Konstfack experimented with different art styles and materials and then also studied architecture did not seem to fit into the picture at the time, let alone into a fixed framework. One thing is certain in any case: it is worth uncovering their large footprints and not being satisfied with a few small footnotes.