Text Sarah WETZLMAYR

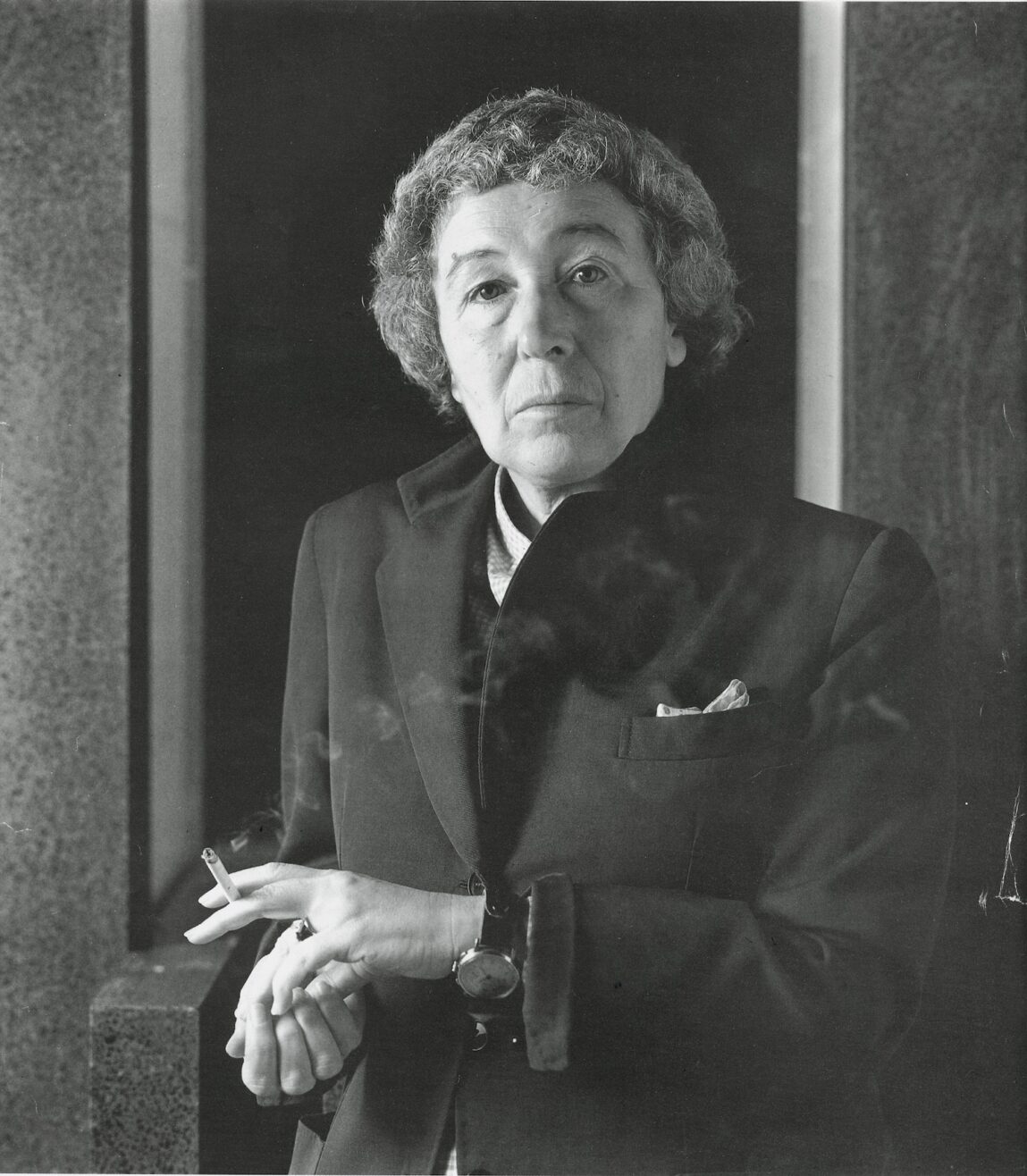

»I like things that change«, the Italian designer, architect, set designer and author Gaetana »Gae« Aulenti once said in an interview. She claimed this form of mobility for herself and her work – throughout her life she resisted categorization and responded to the apparent lack of a signature with the words: »Style means the repetition of an idea that is always the same.« A look back at the life’s work of the designer, who died in 2012.

»The whole world is a stage and all men and women mere players. They come on and go off again«, according to Shakespeare’s comedy »As you like it«. However, the metaphor of the world stage, which has been omnipresent ever since, not only exposes people as the owners of a multitude of roles, but also raises the question of how this stage-like world is constructed. In short: if the world is a stage, do we move through it like a huge stage set?

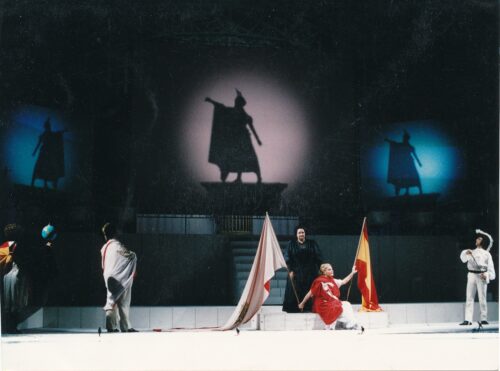

The stage set designed by Gae Aulenti for Ronconi’s production of the Rossini opera »Il viaggio a Reims« at the Vienna State Opera, 1988.

If you look at the work and underlying approach of Italian designer and architect Gae Aulenti, who died in 2012, you feel confirmed in this comparison. Not only because Aulenti’s extensive repertoire of roles also included that of set designer – she worked primarily with director Luca Ronconi – but also because she always saw people and buildings as two interacting parts of the same play. According to Aulenti, », the space, as a co-player or partner, should always be designed in such a way that it allows for different behaviors and does not restrict them.«1 Despite its inherently static nature, it has a mobility and creative power that is also at the heart of many stage designs.

Table Tavolo con Ruote, FontanaArte, 1980

Gare d’Orsay before its conversion into a museum

SENSITIVITY TO WHAT IS FOUND

Gae Aulenti, who as an architect and designer made tables roll (Tavolo con Ruote) and transformed train stations into museums (Gare d’Orsay), was always interested in mobility in her work. She once said: »It’s true, I’m perhaps simply against anything that seems static. I like things that change.« The urge to always remain flexible was also reflected in the fact that Aulenti never wanted to be pigeonholed stylistically. In an interview with the design platform BauNetz, the artist, who was born in Palazzolo dello Stella in 1927, answered questions about the lack of a uniform style as follows: »’I can’t work everywhere with one and the same signature. Because it is the place that dictates how something is to be designed. Style means repeating the same idea and the same details over and over again. That has never interested me.« Instead, she is convinced that you always have to start from scratch with every project.

Main gallery of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Main room of the Palazzo Grassi, Venice

This was probably also the case with the works that brought Gae Aulenti international fame. These include the conversion of the Gare d’Orsay in Paris into a museum. It took a whole seven years before the museum was finally opened on December 1, 1986. Aulenti was very keen to preserve the old building fabric as far as possible. Through a series of subtle, sometimes even minimal interventions, she finally transformed the 20th century station into a 21st century museum. She worked closely with the French curators to create the closest possible link between the architecture and the logic of the exhibition. »My design itself was like a big machine that we drove into the station«, she once summed it up in an interview. On a design level, it was important to her to connect the spaces in such a way that their size did not create a feeling of anxiety or overwhelm for visitors. According to Aulenti, you always have to discover the possibilities hidden in old buildings, not imitate or copy what is already there, but try your own interpretation. »You have to work against the space and still respect it.«

In 1980, the Italian designer and architect was also the first woman to win a project of this size in a competition. In an interview, she once remarked that the renovation of the Gare d’Orsay had given her more strength in this respect. »Back then, people didn’t believe that a woman could design a large project on her own.« Working as a woman in a male-dominated industry did not exactly make it easy for Gae Aulenti to live up to her own ambitions until her breakthrough in the early 1980s. »It took me many years to be able to realize big projects, but I went along quietly, without protesting and without allowing this fact to penetrate my consciousness too much. Aulenti was also only one of two women to graduate in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1954.

Gae Aulenti’s redesign of the Museum of Modern Art at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the conversion of the Palazzo Grassi in Venice for museum purposes also caused a stir. Most of her architectural projects combine a careful adaptation to the built environment, but without wanting to exclude contemporary influences. Aulenti is generally associated with Neoliberty – an architectural movement that was based on the tradition of Art Nouveau – Stile Liberty – which was only very weakly developed in Italy anyway, and which attempted to distinguish itself from the modernism of the interwar period through a stronger historical orientation. In connection with her work, however, Aulenti herself spoke far less about stylistic features than about the unconditional embedding of her buildings in urban contexts. As the former Italian president Giorgio Napolitano noted, her designs were characterized by a great sensitivity for the existing.

April chair, Zanotta, 1964

ICONIC OBJECTS

As early as the 1960s, Gae Aulenti succeeded in gaining a foothold as a furniture designer and designer of industrial products. In 1962, her first commercial furniture projects were launched by the manufacturer Poltronova: the rocking chair Sgarsul, inspired by Thonet’s cantilever chair No.1, and the Stringa chair and sofa series. The iconic Locus Solus armchair from 1964 is part of a collection of garden furniture published by Poltronova. Her interest in industrial design soon led her to collaborate with the most important companies in the sector – in 1964 she created the April folding chair for Zanotta, the following year the Jumbo marble table for Knoll and in 1974 the 4794 polyurethane chair for Kartell.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Photo_Locus_Solus.jpg), https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/legalcode

Series Locus Solus, Poltronova, 1964

Her most iconic designs also include the Pipistrello lamp, which is still in production today and is probably one of Aulenti’s works most influenced by the neoliberty movement. Like her designer herself, however, the lamp does not really want to be categorized. Because the Pipistrello was originally intended for the Olivetti showroom in Paris, it had to stand out all the more from the typewriters and computers that primarily populated the room.

Pipistrello lamp – originally intended for the Olivetti showroom in Paris.

Aulenti made a name for herself as an interior designer with the design of the showrooms for the typewriter manufacturer Olivetti in Paris (1966/67) and Buenos Aires (1968). The Italian car dealer Fiat commissioned her to design the showrooms in Brussels and Zurich (1969/70).

THE LIGHTNESS OF BEING

»Stage design, design and architecture always came together for me«, said Gae Aulenti in an interview two years before her death. The extent to which this is actually the case can be seen, for example, in Aulenti’s Rossini chair made of wood and metal. Designed in 1984 for her stage set for Ronconi’s production of the Rossini opera »Journey to Reims«, the chair was later produced by Maxalto/B&B Italia. But it is not only these clearly demonstrable connections between the stage universe and reality that bring these two worlds so close together in Aulenti’s case that one can actually speak of a world stage. To summarize, it can perhaps be said that Gae Aulenti was concerned with a certain lightness in both areas – with spaces that, despite their size, do not frighten the users and with stage sets that make the players take off. Even literally, because for the »Barber of Seville« she had the singers lift into the air. »The characters fly, yes, they fly«, Ronconi put it in a nutshell.

So it’s all just a game? I don’t think you can say that either. But maybe like this: as in a theater or opera production, Gae Aulenti combines different disciplines in her overall work to create a harmonious, artistic production.

ARTICLE FIRST PUBLISHED IN CHAPTER №VIII »ELEMENTS« — SUMMER 2023