TEXT Lutz Fügener

There is something mystical about this design process. At least from the perspective of the design consumer. Given the ubiquitous presence of design in our product-filled environment, the endurance of this mystery is remarkable. After all, all consumer products without exception and most capital goods, which are often undervalued in this respect – from ballpoint pens to computer tomographs – are based on a multitude of design decisions and/or concepts. In quantitative terms, design is therefore anything but rare – which doesn’t really give it a good prerequisite for lasting exoticism and unapproachability.

One might think that it is in the designers’ interest to preserve the aura of genius and therefore incomprehensibility in their work. They would keep themselves and the results of their work free from well-founded criticism and make life easier for themselves. However, this attitude and the resulting layer of protection came at the price of a huge compromise: the discipline of design, which is already almost defenceless against encroachment and protected neither by state qualifications nor by chambers, has finally become a self-service store for amateurs and self-promoters. The relevant news channels are full of success stories of B or C-list celebrities who became designers overnight. A more astonishing metamorphosis is rare in other professions. There is a long list of professions that include jobs that we all do well or badly in our private lives. Hairdressers, drivers, window cleaners, bakers, cooks and so on. Hardly anyone who manages to spoil their guests with a successful meal claims to be classified as a professional chef. It would be seen as presumptuous––and rightly so––because it is by no means enough to simply produce something enjoyable. This threshold is even higher for safety-related professions. Laws restrict the drive of amateur surgeons or autodidacts in the cockpit of an airplane, because overconfidence becomes an acute safety problem here. This does not seem to be the case for design––at least not immediately.

Cadillac Studio, 1960

»Color Room« at General Motors, 1956

DESIGN SHOW INSTEAD OF COOKING SHOW

And just to make it clear––nobody becomes a designer overnight. Behind the amazing stories of enlightenment are professional marketing concepts and a team of experts who then do the actual work. The development of collections for outerwear, shoes, jewelry (to summarize the most common incarnation miracles) requires expertise in materials, cuts, production processes, sustainability, processing techniques, marketing, ergonomics and much more. If a person’s popularity appears to be conducive to marketing, he or she is occasionally granted one or the other, within certain limits, control and freedom of choice in order to make the design story halfway plausible. This is then staged in a visually stunning way and eloquently reported. In most cases, however, the cooperation of the new designers is limited to signing the advertising contract. None of this would work if the design process were as well-known, comprehensible and public as the cooking process. Design show instead of cooking show––why not?

ACTION FRAMEWORK AND SEQUENCES

The vagueness of the public image of these design processes is its problem and its strength. Once the input data and tasks have been formulated, creative, uncritical phases alternate with critical, analytical and selective phases. In the process, the scope of action contracts step by step and the depth of detail increases. Depending on the complexity of the product, sometimes the phases of such a process are not even clearly visible. These sequences are easy to understand in design processes that are worked on by large teams, as all protagonists need to understand the status of the work and therefore need to communicate. An example of this latter case is the automotive industry with its design studios with up to three-digit numbers of people.

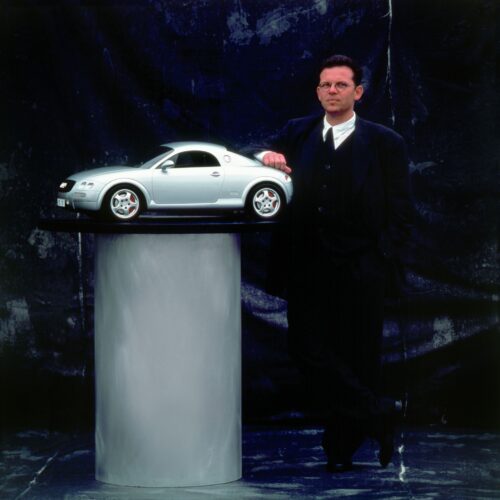

Peter Schreyer with a model of the Audi TT.

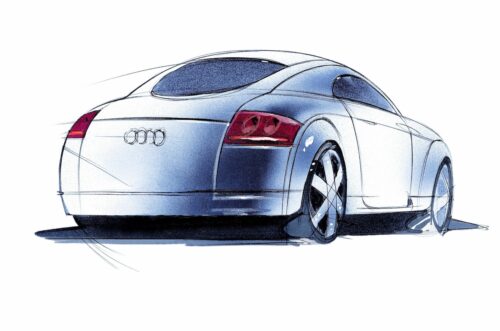

Audi TT Coupé (sketch)

THREE INGREDIENTS

Three ingredients are necessary for a successful design process: Firstly, the ability to produce an unlimited number of ideas and approaches. This is where the intuitive, the »Surprising yourself« plays a role. This phase probably creates the greatest mystery. But there are techniques for this too. Secondly, the ability to make selections, to recognize good things -indispensable for anyone who leads a design team or even an entire studio. And finally, the ability to implement finished ideas and/or concepts with functional and aesthetic quality––the so-called design craft. An ingredient that is definitely no less important, as it determines the first level of perception for recipients and thus the intuitive classification of good or bad, exciting or uninteresting. Particularly in our environments overcrowded with products and information, aesthetic authentication is the first hurdle to overcome in the race for attention. And here we are again with the most pervasive of all clichés about the tasks of design: aestheticization – in the worst case, decoration.

Audi design team, archive photo

ON A SOCIAL LEVEL

Generalization or specialization––a question that is difficult to answer about the training of designers. Of course, both approaches exist in practice. What is often created in small design offices as a single task or by a single person is distributed in larger structures according to inclination or specialization. In the automotive industry, which is known for the division of labor in its development process, it is still common practice today to link designs or design responsibility for a particular design with the name of a designer. An approach that is certainly justified, as this one person usually stands for the original idea, is responsible for continuing to work on it and/or has been entrusted with orchestrating the design project. However, there are also companies in which the lead designers generally claim the rights to authorship. At first glance, this approach is not completely absurd, as designers and decision-makers are inextricably dependent on each other, as success actually depends on the congeniality of this collaboration. While designers produce design proposals in the non-critical phase, the decision-makers select these works in the critical phase and create the basis for decisions for the next work sequence of the designers. What one person does not design, the other cannot decide on, but the final shape of the design depends largely on the cascade of these decisions. This is where teamwork and in-process communication––explicitly also on a social level between the protagonists––play an important role.

Design sketch Kia, with the characteristic »Tiger Nose« developed by Peter Schreyer.

UNPREDICTABILITY OF THE GENIUS

The potential of design as an important productive force is undisputed. Internationally prominent designers such as Jonathan Ive, who is inextricably linked to the history of the Apple brand, or Peter Schreyer, former chief designer at Audi and highly revered in South Korea in particular thanks to his work for Kia/Hyundai, have significantly increased, doubled or even multiplied their companies’ profits through their work and helped their respective brands to achieve sustainable value. However, from the perspective of the entrepreneurs or CEOs responsible, these grandiose success stories harbor the danger of unpredictability and unrepeatability. It is easy to be catapulted to great heights by the design boost, but dependence on the non-evaluable outpourings of genius creates unrest in management and among shareholders at the latest when the success curve slowly begins to flatten out. In the best-case scenario, these design personalities have managed to implant their way of thinking and working into the internal system, making them resilient to their own loss––or, one could say, making themselves resilient.

Design in progress – analog and digital.

»DESIGN THINKING«

It was not least this need that gave rise to the idea of describing the structure of the supposedly promising design process, stripping it of its mystery and making it reproducible and universally applicable. In the nineties of the last century, the first academic structures emerged that took on precisely this task. The Stanford d.school is regarded as the first institution to set itself the goal of applying the framework of the design process to any other development process. The only prerequisite for the meaningfulness of the application of these processes was that one or more creative decisions were decisive for their success. The idea of »Design Thinking« was in the world and spread quickly. Surprisingly, it also became the buzz word in design education in the early 2000s, which, viewed from a distance, is tantamount to the proverbial »carrying owls to Athens«. Presenting design with its very own way of doing things in new packaging sounds like a bold marketing approach. However, applying this approach to other sectors––from the design department to the insurance company––actually led to new approaches, relevant results and, not least, exciting experiments in the social structures of the respective departments, as new team formations called old structures into question.

THE IRONY OF IT ALL

An exciting aspect of the applied systematization of the design process has recently emerged through the increasing access to artificial intelligence tools. Almost at the same time as text-based applications, their image-based counterparts have become available and have since challenged the academic and professional structures of the design industry to take a stand. Serious observations with a scientific approach and experiments on the practical applicability of AI in the design process are also already available. The dissertation by Steffen Reichert on the application of AI in the automotive design process (Steffen Reichert, COMPUTATIONAL DESIGN METHODS FOR THE DESIGN OF AUTOMOBILES; University of Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-9819457-3-7) deserves special mention here. AI appears to be an effective means of accelerating the process, particularly for the non-critical phases of variant generation later in the project and thus after the original ideas of the design have been defined. When the disruptions that cannot be performed by AI are no longer required and the formal elaboration begins, AI can take over the hard work of the designer, who is only required to a limited extent in terms of craftsmanship, by cleverly defining »sliders« and deliver the results in seconds. And that is just the beginning of the considerations. The automotive industry, challenged by the constant demand for shorter development times, is already in the experimentation and testing phase in various areas. If the problem of confidentiality in the use of online applications can be mastered, these efforts will intensify once again.

However, there is also an irony in this approach. The design process, which is now transparent and recognizable in its structure, would be operated in phases by self-learning computer systems whose decision-making paths are not comprehensible in the specific case. Between the input values and the result lies a land that cannot be entered by the operators. A mystery.

Article first published in CHAPTER №IX »WORK IN PROGRESS« — WINTER 2023/24